The idea for this exhibition come slowly and fortuitously. In some senses it is a reaction to the dwindling supply of ‘good’ paintings. Those that surface are snapped up by the established dealers, who will then sell them on to the great museums and galleries, where they will be seen and appreciated, safely away from the art market.

It also brings together pictures which bear little stylistic resemblance to one another, but share various things in common. The most important being quality. it is often very hard to put in measurable terms what is meant by ‘quality.’ Tastes are subjective and quality will depend on the eye of the beholder. But the existence of national museums and established galleries, suggests that there is a vague consensus on what belongs in a museum and what does not.

But the road from ‘forgotten talent’ to ‘academic reassessment’ to ‘museum acquisition’ is a convoluted one, which I suspect is best begun in small and practical steps.

1. Framing

2. Conservation

3. Photography

4. Research

Bad frames destroy the perception of good paintings and the works of obscure artists are generally framed very badly. Such paintings might once have had appropriate frames, but it is likely that over time these have been taken away and given to more ‘worthy’ pictures. First impressions are significant, but they can also be misleading. Dealers and collectors tend to search through online search engines with small images. The sheer scale of the auction system necessitates a rapid scouring of catalogues and because frames are generally less complex than the paintings themselves, the human mind forms a quicker picture of their relative merits.

In a discordant whole, the human gaze is drawn to the weakest aspects and it is often very difficult to distinguish a good painting from a poor frame. Even the best paintings, held in faux-gilt frames, will forever conjure the image of a suburban living room, as opposed to that of the galleries or museums where it should belong.

The same is true of sympathetic conservation, which is costly and time consuming. It is therefore generally reserved for more profitable paintings, and it takes some measure of imagination and experience to see past the well-intentioned, but misguided remedies of previous owners.

Just as the invention of an improved stereo record made it possible to fully appreciate the music of an overlooked and misunderstood Gustav Mahler, recent advances in photography have liberated talented figures from the art historic wastelands. But professional photographs remain expensive, because the camera, lighting and all the equipment that constitutes a professional studio is expensive. Beside this, perhaps the most costly factor of all is a well-trained and experienced photographer. Even the best paintings look appalling under the wrong light. Crisp, modern photographs, taken under the right conditions are absolutely necessary to demonstrate the true qualities in any painting.

Framing, conservation, photography can reframe the paintings themselves, but research can revive the reputations behind them. In that sense it serves as a way of reframing the contributions of forgotten figures. Paintings that are easy to research are hard to buy. Paintings which are hard to research can be bought more reasonably. The same principle is true of most things. A house that is difficult to repair is cheaper than one which can be repaired easily.

I believe there are many ways of repairing the reputations of forgotten artists. I hope that this catalogue will demonstrate some of them.

Circle of

In the art market, ‘circle of’ has been devalued to the point where it is largely meaningless term, denoting little more than a vague resemblance to the work of someone more famous. This is a great shame for it is actually a very accurate description of human life. All people live in circles and even the most mundane routine collides daily with a loose network of friends and acquaintances. With creative people this is even more the case, as the process to produce and innovate depends above all on social interaction. An influential artist will inevitably accumulate a circle of friends and followers.

When faced with an obscure but talented artist, it is generally necessary to piece together their life through their influences, education and known works. The places they lived and the figures they associated with.

That one artist might have lived in close proximity to a greater artist is not by itself an indication of talent, but it can be comforting to know that they were valued by their contemporaries. It is also interesting to see that they once swam in significant historical currents.

Such a process might invariably reveal their decline to have been accidental or unjust. The results of small but significant decisions, taken at critical moments in their life. In this regard dates themselves can be important. Some painters die prematurely; others are born to soon. That Francisco Sancha died in September 1936 is by itself not especially significant… before remembering that the Spanish Civil War had just begun and that he had spent the vast majority of his life contributing to radical journals. Emile Charlet was born a decade before his more influential brother Frantz, and was living in Paris when his brother and friends came to found Les XX in Brussels in 1883.

James Watterston Herald (1859-1914)

Sometimes it is precisely through isolation that an artist falls into obscurity. Two Scottish painters in this exhibition: David Waterson and James Watterston Herald, both renounced successful careers in artistic centres such as Paris, London and Stockholm to live and work in their native towns. Possibly in the case of Herald so that he might drink in the comfort of his local pub. Neither artist seems to have cared for fame or self-promotion; Waterson sold his works from the local stationers, and his life seems to have been one long evasion of the unfortunate fact that artistic success depends as much on business practice as it does on talent.

A similar thing is true of Gertrude Hadenfeldt, who didn’t merely defy the conventions of her period, but was actually largely oblivious to them, spending much of her career painting alone in the remote parts of India and the Himalayas. She never married or had a family.

Perpetuation of artistic legacy will generall fall to those close to a painter: friends, family members, collectors - all with an incentive to lay out the details of their life, when the knowledge is still fresh in the mind. Wise artists outsource the messy business of self-promotion to their immediate circle.

There are further obstacles for female artists and more qualified writers will have written at length on the various societal and cultural factors which impede their development. I will focus on the more practical problems they face. Marriage leads to a changing of names, which in turn can displace a promising early career from its later period. Early marriage tends to produce a family, and therefore a situation which does not necessarily lend itself to the singular and selfish devotion of artistic life.

Anna Massey lea Merritt (1844-1930), a talented painter affiliated to the pre-Raphaelites surmised that:

"The chief obstacle to a woman's success is that she can never have a wife. Just reflect what a wife does for an artist: Darns the stockings; keeps his house; writes his letters; visits for his benefit; wards off intruders; is personally suggestive of beautiful pictures; always an encouraging and partial critic. It is exceedingly difficult to be an artist without this time-saving help. A husband would be quite useless.”

With modern amenities such as washing machines, central heating and the like, it is sometimes difficult to get a sense of the vast amount of time that historically might have been spent on the everyday tasks of running a home. Two artists in this exhibition, both for different reasons seem to have suffered from these realities. Grace Elizabeth Gladstone studied at the Sydenham School of Art before winning a scholarship to study at the Royal Academy in 1894. She married shortly after, changing her name and settling into the family routines that would make the life of an artistic difficult. William Dixon’s refusal to employ domestic servants (something he could have easily afforded) was directly to blame for his inability to capitalise on his undoubted talents. Some artists do not pursue immortality, others are temperamentally unsuited to success.

War

As in life for the individual and for the collective, war obliterates previous norms, disrupting economic and cultural activity. In some cases it curtails entire movements. Kandinsky’s ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ was founded in 1911, only to disband in 1914, when many of its members suddenly found themselves united in artistic ideals but fighting from opposing trenches. Galleries close; social interaction, the true currency of all artistic endeavour, ceases. Conscription draws talent away from their chosen roles and enlists them for the battles which will invariably claim life. Even if a promising young artist does emerge unscathed from war, then they have often lost key years in their development. And resuming their studies at an older age, they quickly find that they have lost the optimism and vitality of their youth. Promising careers are therefore shelved or resumed on less energetic terms.

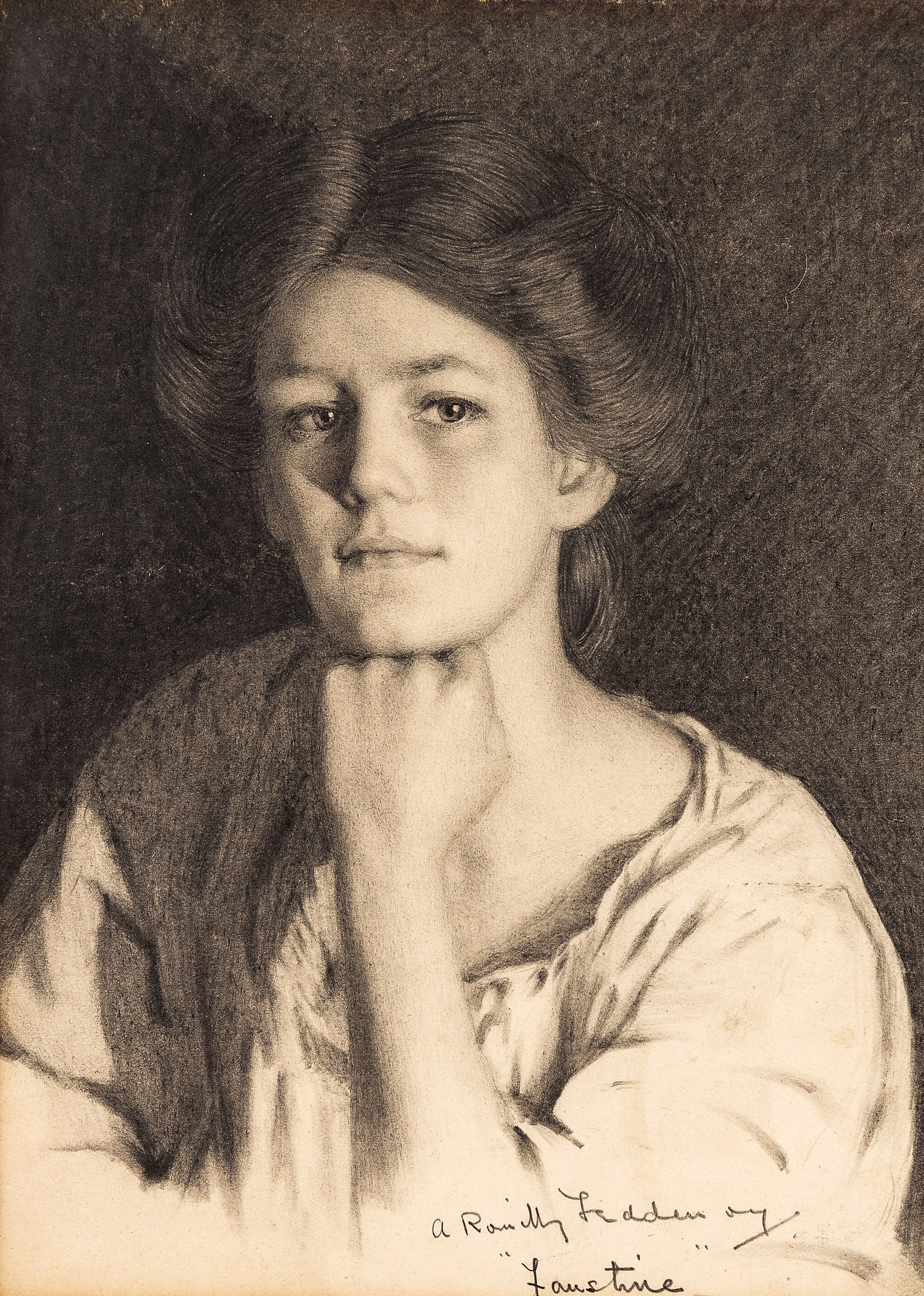

This is almost certainly the case with George Duncan Macdougald and Romilly Fedden, both of whom were coming into their own in the years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War. Post 1918, Fedden retreated from artistic life and authored a manual on fishing, a direct parallel to how Izaak Walton escaped the horrors of the English Civil War to write the 'Compleat Angler' in 1653.

Macdougald’s post-war career descended into a narrow parochialism, lending his skills to a series of stylish war memorials and plaques. It is also possible that the economic depression following a world war is the reason that MacDougald worked with bronze before the war and canvas and paint after it.

It is also worth pointing out that War can have the opposite effect, bringing artists into contact with subjects that they could not have found in peace. It also brings together persons who could not have known each other in normal times.

Fashions and Taste

Some artistic movements are influential enough to attract many followers, but too large for all of them to be recognised. The periphery of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood is awash with talented figures, briefly animated by the spirit of the time, but swiftly forgotten, save for a few impressive works. Such pictures serve as a passing zenith in quiet careers, living proof that even middling painters can have their moments.

Artists capture the spirit of their own age, or perhaps (unwittingly) the spirit of a another one. It is also possible that an artist can outlive the stylistic period to which their works belong. Edward John Poynter (1836-1919), the great Victorian neoclassicist lived well into the twentieth century and therefore found that at the end of the life he was painting for a less sympathetic age.

Female artists are especially vulnerable to this strange fact, with their obscurity stemming not from premature death but from remarkable longevity. Gertrude Hadenfeldt and Grace Gladstone both died in their nineties, outliving their family, friends and close acquaintances.

Inspiration and Consistency

Though ‘inspiration’ can account for a few fine paintings, consistency is the measure of the great artist and Aristotle may well have had a point, with his “we are what we always do.” Though the potential for genius is innate, the circumstances that allow its cultivation are not. Not all geniuses have the luxury of applying it in narrow fields. Many are buffeted by daily life and can therefore not afford to be artists, least of all artistic geniuses.

It is hard to tell if Sir Thomas Lawrence’s remarkable consistency afforded him the best clients, or if the pressures of such commissions brought about an urgent need for consistency. Whatever the cause, the consequence was that his posthumous destiny was entwined with that of great historical figures, many of whom could afford to pay him well enough so that he may afford better materials than his competitors. His paintings are therefore in perfect condition, displayed in places where they will have a better chance of imprinting themselves on the collective memory.

Artists are inconsistent, but especially those of inconsistent means and habits, and it is common to see a middling painter rise to improbable levels at certain points in their life. Some enjoy fertile periods in their youth, before the demands of adult life have had a chance to assert themselves. Lucrative commission can also liberate from the more immediate pressures of making a living, allowing an artist to invest money and time in painting a compelling image. By comparison it is risky for a struggling painter to produce labour intensive works without having a certain buyer and it is difficult to push boundaries when you are relying on the tastes of the paying public.

Short term successes quickly become long term advantages. Influential patrons beget further patronage. Better quality materials distinguish successful artists from their competitors. Sir Thomas Lawrence bankrupted himself in procuring the best pigments and as a result his paintings have remained largely unharmed many years after his death in 1830.

The ability to invest time and care in a painting is also the luxury of a comfortable life. Equally important is the lottery of the hanging committee, where jostling for the most favourable wall space, many artists have been left disappointed. Benjamin Robert Haydon’s 7ft portrayal of Dentatus was hung in a darkened recess in 1809, leading to a lifelong quarrel with the Royal Academy. Initiative when surrendered, is seldom regained, but many artists never have momentum to relinquish.