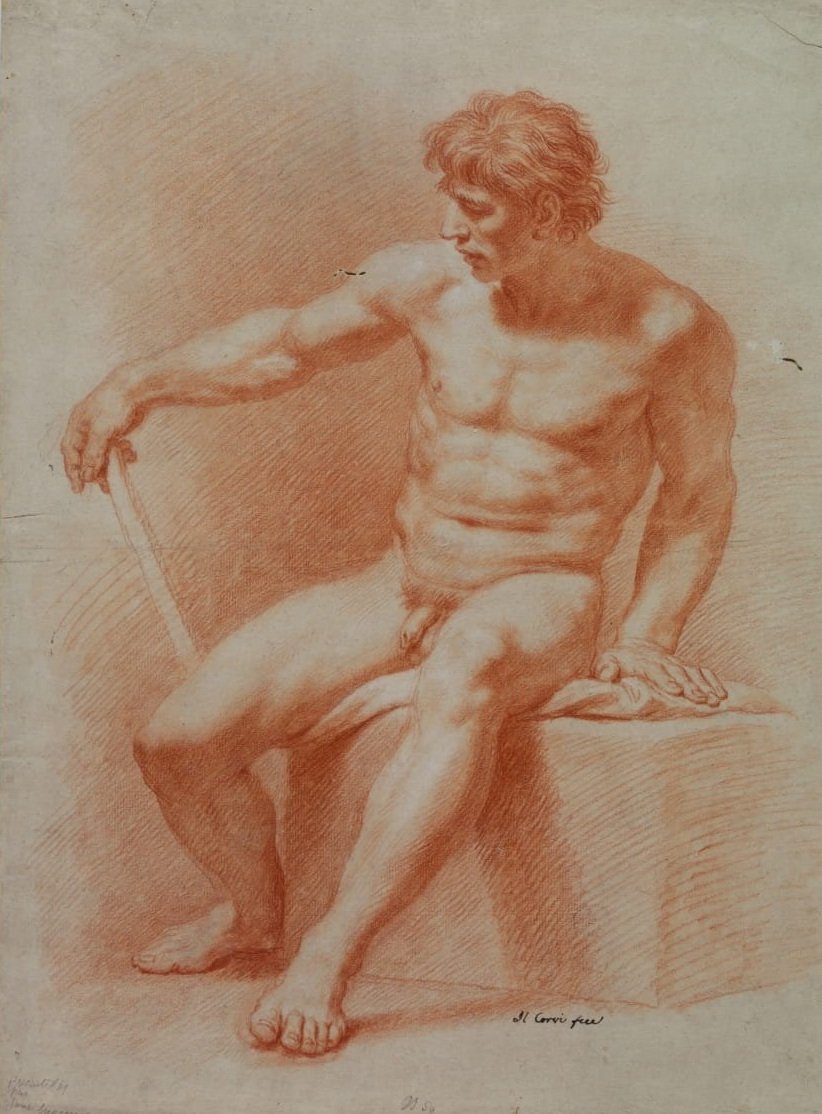

Domenico Corvi (1721-1803)

Reclining male nude (c1760) 🔴

Black and White Chalk on Laid Paper (Fleur de Lis Coronet watermark)

Dimensions: 495 x 390mm

As well as being a significant reappearance in the scant oeuvre of Domenico Corvi, the present study reveals why he was once considered the equal of Anton Rafael Mengs. Unlike established masters, whose works are valued for their rarity, scarcity in forgotten masters is often an impediment and just a handful of Corvi’s academic studies have come to market in the last 30 years. Other comparable examples, visible in public collections like the Smithsonian and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, offer glimpses of his capabilities as a draughtsman.

Corvi’s ‘academies’ were coveted in his own lifetime and by those close to him. Luigi Lanzi (1732-1810) records his command of the human form and suggests his drawings were “very precious” and “more sought after than his paintings.” The sculptor Vincenzo Pacetti (1746-1820), a noted collector, acquired 21 of them shortly after Corvi’s death.

Domenico Corvi was born in Viterbo in 1721. He moved to Rome at the age of fifteen and joined the studio of Francesco Mancini (1679–1758). Much of his early career was spent decorating Roman churches. He also seems to have worked with Anton Rafael Mengs (1728-1779); Henry Benedict Stuart, younger brother of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, sat for both painters in 1747.

Self Portrait - Domenico Corvi (Accademia di San Luca, Rome)

At the age of 29, he won first prize in a drawing competition at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. Just seven years later he was a director in the same school, presiding over life classes at the Accademia del Nudo. Corvi served frequently between 1757 and 1802 and it is telling that his self-portrait of 1785 shows him with a nude sketch; normally the kind of work dismissed for its functionality.

Finished drawings of the academy nude — called academies — were regarded in a sense as the touchstone of professional excellence. Far beyond student years, and unrelated to preparations for specific work, academy drawing remained a common exercise for mature artists, who viewed continued study from life as a necessity in maintaining and perfecting their skills as draughtsmen.

Academy drawings by the masters often remained in the studio as guides for students, and just as this seems to have been a regular practice by the later seventeenth century, so in the early 1780s we similarly learn that a young painter freshly introduced to Batoni’s studio was given several of his master’s academies to copy as a first assignment.

Prized by connoisseurs, academy drawings formed an essential category in any representative collection. Batoni could confidently offer one to a patron as a token of regard, and Lanzi reputed that Domenico Corvi’s drawn academies were in even heavier demand than his paintings. For the critic academy drawings offered a crucial standard of judgment as [Pierre-Jean] Mariette illustrated around 1770 when, in criticizing Raphael Mengs, he saved for the coup de grace a remark on the artist’s academies: “I have seen some of his drawn academies: they are of ice.”

Ulrich W. Hiesinger

Provenance

The ‘Il Corvi’ inscription, visible on other academic studies, including one at the Smithsonian, is likely that of Count Alessandro Maggiori (1764-1834) [lugt 3005b], who amassed a significant collection of Italian drawings, whilst living in Faenza, Bologna, Naples and Rome between 1785 and 1810.

Following Maggiori’s deah in 1834, his collection of nearly 3,000 drawings was dispersed and examples can now be found in most major museums, including the British Museum, the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 150 of these were acquired in 1925 by the municipality of the town of Monte San Giusto and form the nucleus of the Centro Alessandro Maggiori there.

Nude man seated - Domenico Corvi (Red Crayon) Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum