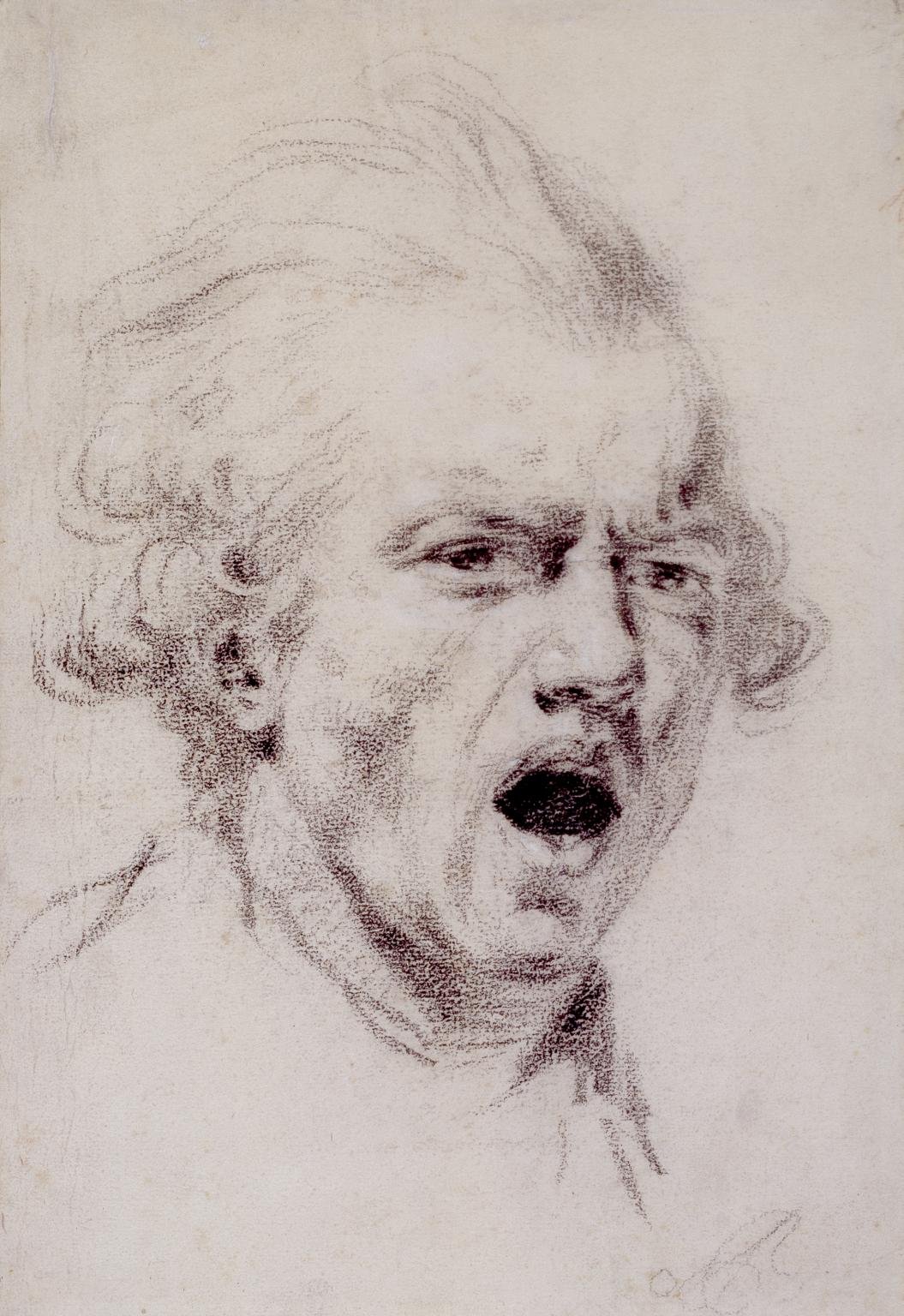

Charles Verlat (1824-1890)

Tronie or Self Portrait as a Man in Terror 🔴

Signed and Insrcibed: “1er Concours 2 Charles Verlat Natif D’Anvers 1844”

Charcoal (and Chalk) on Paper

622 x 451mm

Charles Verlat’s contribution to the ‘Concours’ at the Royal Academy of Antwerp in 1844 shows the influences of many masters. From Rembrandt’s open-mothed expression of surprise to Sir Joshua Reynolds half-hearted attempt at conveying horror, while remembering that little could be as horrific as a President of the Royal Academy showing his teeth in public.

Perhaps such studies of human emotion are best left to the students? It is interesting to see the great teacher as a student. Verlat believed that art schools should not waste time teaching colour - an innate instinct of any painter capable of being an artist – but instead should devote themselves to studying the human form, perceiving like the old masters, that drawing was the best form of study.

Writing in 1895, Max Rooses (1839-1914) said of him that “not since the death of Rubens had the Antwerp School known so strong and imaginative an artist.” He describes an “excellent draughtsman, of unparalleled neatness, and of unusual delicacy, when he wished”, suggesting that his drawings looked as if they came from the copperplate. But drawing seems to have been a means-to-an-end for Verlat, who in later years was known to have stopped altogether, becoming “too impatient, too sure of his hand…” to set out his designs before painting.

Perhaps this was inevitable in a figure that came to resemble the Belgian Landseer and Lord Leighton in a single artist. And though he painted for both of them, (a two year tour of the Holy Land yielded 49 large canvases), he typically worked for just 5 hours a day, likening himself to the “thoroughbred… which, after several laps of the racecourse, is more weary than the mule which has trotted from morning to night.”

Self-Portrait as a Figure of Horror, c1784

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Chalk on Paper (Tate Britain)

Such self-confidence (and praise) seems incongruous for a now largely forgotten figure, whose works spanned the full range of the academic hierarchy, from still lifes to religious scenes. Versatility is rarely a blessing when it comes to building an artistic reputation and history has found it difficult to unpick this artistic range.

Self Portrait /“The Surprise in Terror” c1790 - Joseph Ducreux ( 1735-1802)

Oil on Canvas (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm)

“Skull with a Burning Cigarette” c1885-1886 -

Vincent van Gogh

Oil on Canvas (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam)

Verlat & Van Gogh

I can assure you it’s not a bad sign if people like Verlat...demand that of someone. For there are enough of them that Verlat simply leaves to get on with it because — they just aren’t the fellows for the loftier figure.

Vincent van Gogh

(letter to his brother, Theo, January 1886)

Vincent van Gogh entered the Royal Academy of Antwerp in 1886, at a time when the school was known as “Verlat’s.” He wasn’t expelled and though he remained for just a few weeks, clashing with the director, both artists recognised genius in the other. Van Gogh kept his for himself; Verlat gave his to the academic system, thus preparing the way for a new generation of artists, who in learning the techniques and conventions of an earlier period, were later able to reject them.

Self Portrait as a Wounded Man, 1844

Charcoal (and chalk) on Paper 501 x 443mm - (with Dominic Fine Art)

Verlat & Courbet

When two artists are known to have crossed paths, scholarship tends to assume that the flow of ideas passes from the leading figure to the lesser-known talent, but this is not always the case and even the most influential painters take inspiration where they find it. It is also possible that good ideas originate in strange places, with as much to do with their time and setting, as they do with the personal judgment of those that conceive them.

These rediscovered drawings, both dating from 1844, would suggest that Charles Verlat and Gustave Courbet arrived at a similar style at a similar time and many years before the two painters eventually met in Paris in the 1850s.

Courbet arrived in Paris in 1839 and spent the early 1840s converting youthful despair into powerful self-portraits. But before being a realist, he was a post-romanticist, indebted to Delacroix and Gericault, but rejecting their excesses. When the Paris World Fair of 1855 rejected his pictures for ‘a lack of space’, he erected the “Pavilion of Realism” next to the main site and displayed his works alone. This pioneering move likely appealed to Verlat, who attempted a similar thing in Antwerp many years later, when he built a wooden hall to display his 49 large canvases made on a tour of the Holy Land.

Self Portrait as a Desperate Man 1843-1845 - Gustave Courbet Oil on Canvas (Private Collection)

Verlat’s graduation from romanticism to realism was less painful; he came under the influence of the Belgian Romantics, proficient painters unwisely lending their skills to the parochialism of a young country. His time in Paris (1850-1868) threw him into contact with Ary Scheffer and Eugene Delacroix. It was possibly through the latter that he befriended Eugene Isabey, who followed him back to Antwerp, as well as a young Gustave Courbet, who Delacroix was busily defending. Verlat’s friendship with Courbet was the likely reason the French artist exhibited in Antwerp in 1861, delivering his landmark lecture and attracting a host of Belgian disciples, while being shunned at home.

Self Portrait as a Wounded Man 1844-1854 - Gustave Courbet - Oil on Canvas (Musée d’Orsay, Paris )